As a lifelong stutterer, grad school was my public-speaking baptism by fire—I was severely burned.

This was because my first inclination, as with most novices, was to not trust myself. To present my findings and conclusions to a room full of faculty and fellow students, I thought I needed a safety net of well-chosen words on the printed page that perfectly captured the nuances of my arguments. How wrong I was.

No one paid attention to my analysis. Instead, all they heard was my stumbling delivery, my wide-eyed, show-stopping pauses as I tried to overcome every ‘S’ and ‘C’ that triggered my stutter and drenched me in embarrassment.

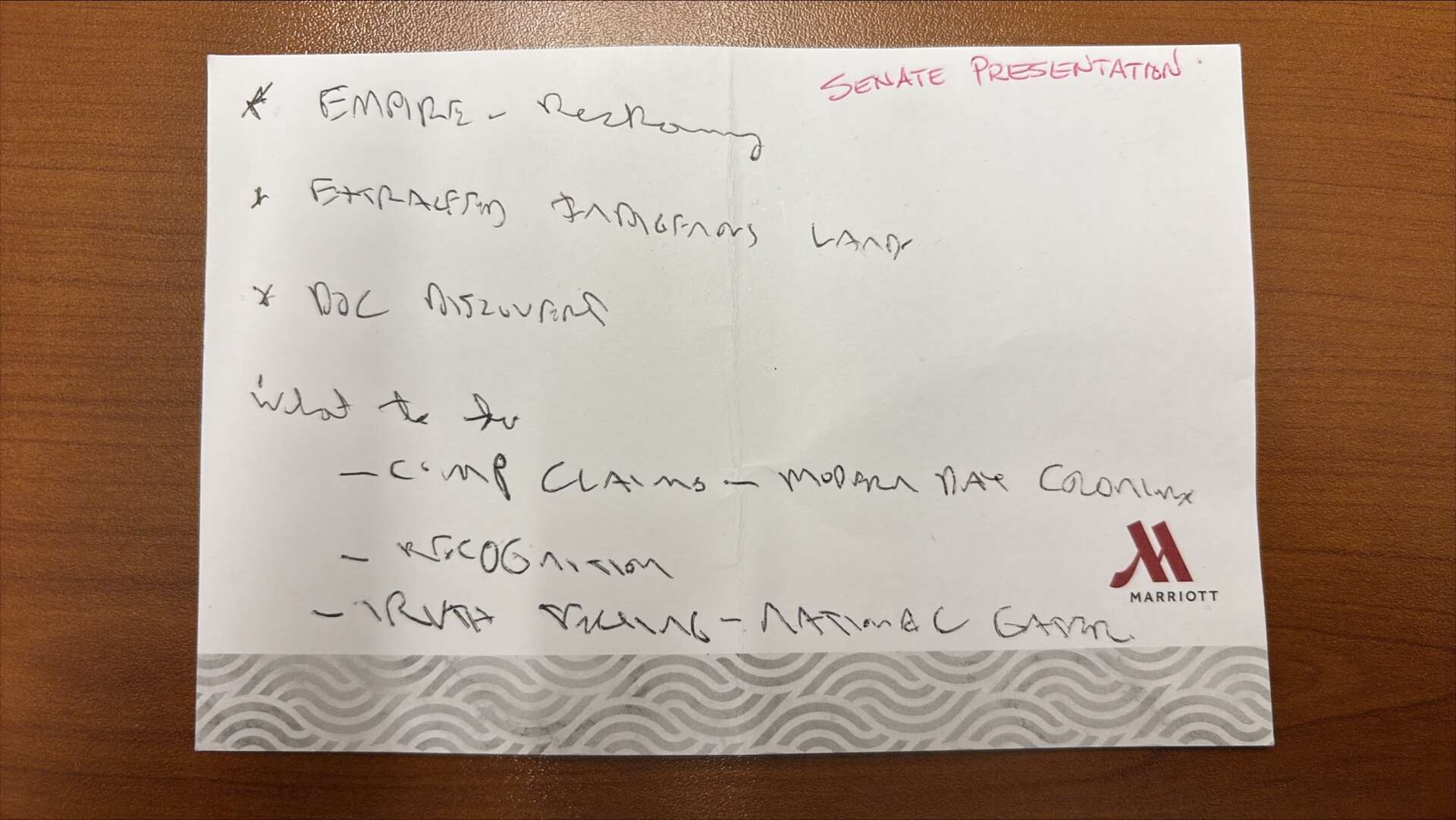

All that seems like a long time ago. Over the years I have gradually abandoned all props. Now when called on to speak in public, the most I do is scribble a few illegible words on a hotel napkin.

Speaking notes for my appearance before the House of Commons Standing Committee on Indigenous and Northern Affairs for its study on the Restitution of Land to Indigenous Peoples – May 10, 2023. You can watch the recording here.

Speaking notes for my appearance before the House of Commons Standing Committee on Indigenous and Northern Affairs for its study on the Restitution of Land to Indigenous Peoples – May 10, 2023. You can watch the recording here.

When I was invited to be part of a recent plenary panel in Vancouver on “Advancing Indigenous Laws through the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples” my hotel napkin of choice was from the Westin Bayshore. The words I scribbled were ‘diligent’, ‘C-92’ and ‘referential incorporation’. What I said surprised me and those in attendance.

When I was asked to speak at the conference, I first confirmed with the organizers whether they were serious. “You do realize, I don’t think UNDRIP is a panacea?”. That’s okay, they assured me. “We want to include different perspectives. Be as critical as you want.”

When the day arrived, and after three espressos, I scribbled my words on the napkin and took the stage along with Indigenous legal experts from B.C., Ontario and New Brunswick. The presentation was informal with the four of us either sitting on a sofa or in easy chairs cradling cordless mics. When it came to my turn, I glanced down at my napkin and began to speak.

To my surprise and almost everyone in the room I launched into a passionate argument for using UNDRIP to create space for Indigenous people to exercise their own laws and inherent decision-making powers. During a response to a question, I admitted to the entire room that my optimism had surprised me just as much as it did them and joked that maybe I’d had one too many espressos. In hindsight, I’ve thought more about what it means to speak the truth.

A First Nation friend and colleague summed it up well during a conversation we had as part of a course I teach on law and governance for the Haida Gwaii Institute. She explained that most of the members of her community do not trust people who speak based on prepared notes or a PowerPoint. Their reaction is to wonder what the person has to hide. If they were prepared to speak the truth they wouldn’t need props. They’d simply open their mouths and speak. They would trust that what they said was the truth, in all its raw, unrehearsed directness.

Speaking the truth in this manner eschews the dominating voice of authority for humility, contingency and surprise. It is to recognize that when we drop the pretense of being a know-it-all expert, we not only connect with our audience, we also connect with deeper truths that are not ours but, if we are lucky, speak through us.

| Bruce McIvor is a member of the Manitoba Métis Federation. His latest book, Indigenous Rights in One Minute: What You Need to Know to Talk Reconciliation will be published May 13. |

First Peoples Law is a law firm dedicated to defending and advancing the rights of Indigenous Peoples in Canada. We work closely with First Nations to defend their Aboriginal title, rights and Treaty rights, uphold their Indigenous laws and governance and ensure economic prosperity for their members.

Sign up for our First Peoples Law Report for your latest news on Indigenous rights