Prime Minister Carney made it clear last week when he met with Indigenous leaders that he doesn't intend to make changes to Bill C-5.

While his government has said it will 'consult' with Indigenous Peoples over the summer, because he won't amend the legislation, this is more political damage control than real consultation.

So now what?

For decades First Nations and the Crown argued in court over whether federal and provincial governments can rely on existing review processes (usually environmental assessments) to fulfill the duty to consult, or whether there is a requirement for custom built processes specially designed to fulfill the duty to consult. The Crown won. The courts said they could rely on their existing processes.

Ironically, with Bill C-5 the federal government has surrendered its hard-fought court victory.

Because everything will turn on a federal decision to designate a project as being in the 'national interest', the federal government will not be able to rely on its existing processes.

This is because their processes won't be activated until after there is a decision to designate. The Supreme Court has been clear--governments can't decide and then consult.

If the federal government says it'll decide a project is in the national interest and consult later through an environmental assessment it will have painted a huge target on itself and the project Indigenous people will be hard pressed to miss.

Having painted itself into a legal corner with Bill C-5, the only way out for the Carney government is to work with Indigenous people to design a custom made process to review pending decisions to designate a project as being in the national interest.

The process will need to be designed from scratch in cooperation with affected Indigenous Peoples. It will have to respect Indigenous decision-making, UNDRIP (including free, prior and informed consent), and the requirements for consultation and accommodation and the justification of infringements of Aboriginal treaty rights set down in Canadian law.

Importantly, because there is no turning back on a project once it has been designated as being in the national interest (it becomes a train guaranteed to reach its destination), the process will have to be more robust and more meaningful than anything we've seen to date in Canada.

In his rush to push through Bill C-5 over objections and warnings from Indigenous people, Prime Minister Carney has made a lot of work for himself.

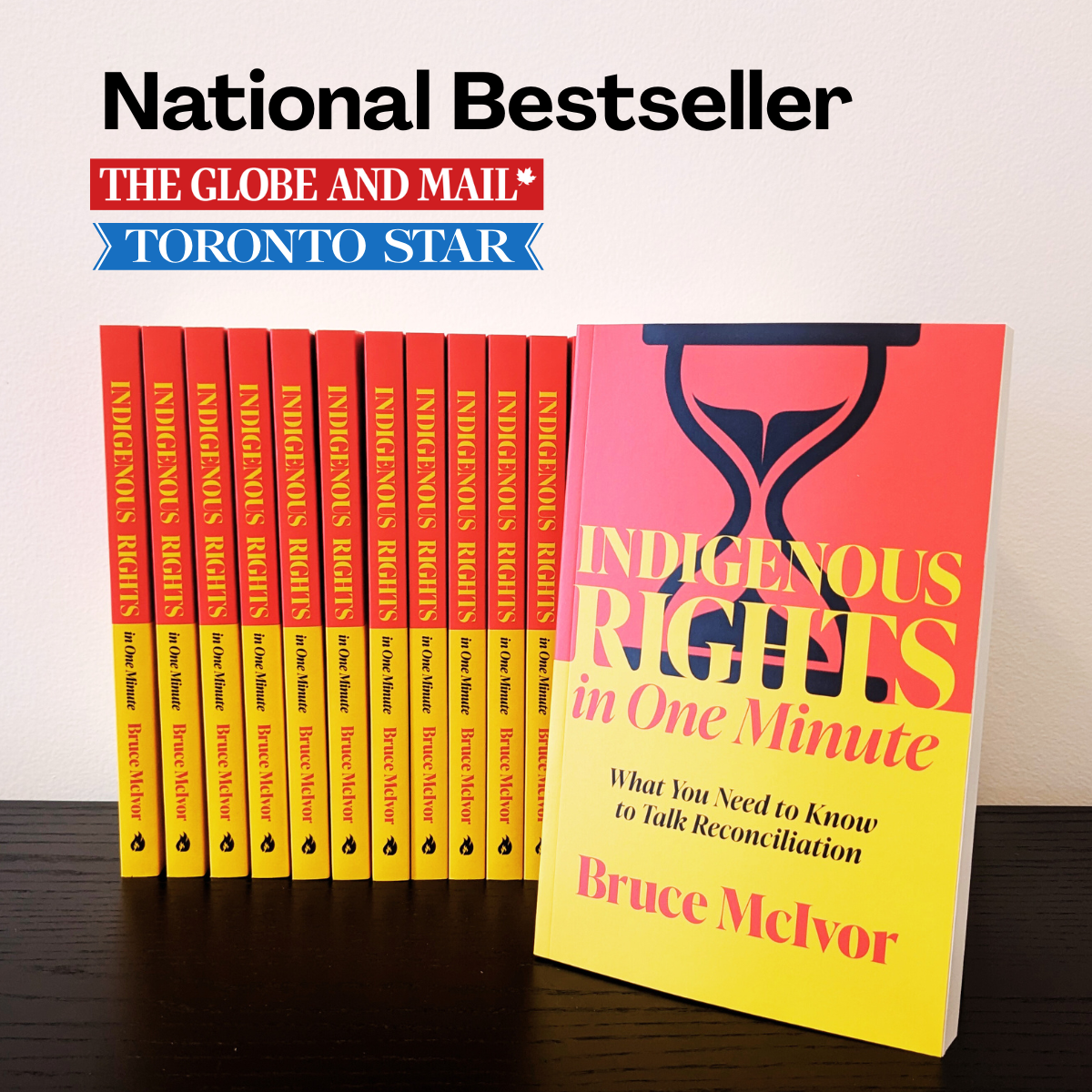

| Dr. Bruce McIvor, lawyer and historian, is senior partner at First Peoples Law LLP. He is also an Adjunct Professor at the University of British Columbia’s Allard School of Law where he teaches the constitutional law of Aboriginal and Treaty rights. He is the author of two books on Indigenous rights: Indigenous Rights in One Minute: What You Need to Know to Talk Reconciliation (2025) and Standoff: Why Reconciliation Fails Indigenous People and How to Fix It (2021). He is a member of the Manitoba Métis Federation. |

First Peoples Law is a law firm dedicated to defending and advancing the rights of Indigenous Peoples in Canada. We work closely with First Nations to defend their Aboriginal title, rights and Treaty rights, uphold their Indigenous laws and governance and ensure economic prosperity for their members.

Sign up for our First Peoples Law Report for your latest news on Indigenous rights