The relationship between the recognition of the collective rights of Indigenous Peoples under section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 and individual rights to freedom and equality pursuant to the Charter of Rights and Freedoms has been a longstanding source of tension and uncertainty for Indigenous communities and their members.

The Supreme Court of Yukon’s recent decision in Dickson v. Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation sheds light on Canadian courts’ approach to addressing these tensions in the context of modern Crown-Indigenous treaties.

What it is about

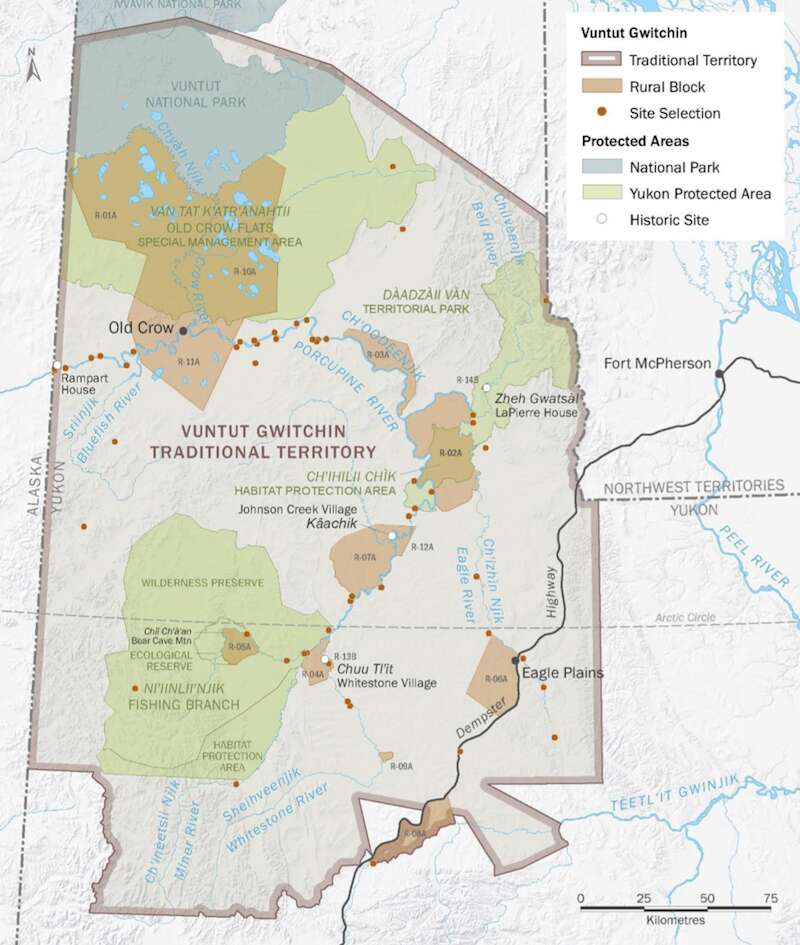

Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation governs itself based on the Vuntut Gwitchin Constitution, which it enacted pursuant to a self-government agreement between Vuntut Gwitchin, Canada and Yukon. The Vuntut Gwitchin Constitution provided that Vuntut Gwitchin council members must either reside in the community of Old Crow or relocate there within 14 days of being elected to office.

Cindy Dickson, a citizen of Vuntut Gwitchin residing in Whitehorse, challenged the residency requirement on the basis that it infringed her equality rights under section 15 of the Charter.

Vuntut Gwitchin argued the Charter did not reflect its legal and political traditions or governance systems and that the challenge to the residency requirement should be brought pursuant to provisions in the Vuntut Gwitchin Constitution, which it described as the supreme law of Vuntut Gwitchin.

What the court said

The Court concluded that the Charter, as part of the Constitution Act, 1982, applied to the Vuntut Gwitchin Constitution, government and laws.

According to the Court, Vuntut Gwitchin’s concern that the Charter did not reflect its legal and political traditions or governance systems was addressed in part by section 25 of the Charter, which states that the Charter shall not be construed so as to abrogate or derogate from Aboriginal or Treaty rights.

The Court held that the residency requirement in the Vuntut Gwitchin Constitution did not, in itself, infringe Ms. Dickson’s section 15 equality rights. However, the Court found that the requirement that a successful candidate relocate to Old Crow within 14 days of the election could create a disadvantage by imposing an arbitrary disenfranchisement on Vuntut Gwitchin citizens who wished to run for council but did not reside in Old Crow. As such the words “within 14 days” were declared to be of no force and effect.

Photo Credit: Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation

Why it matters

The Court’s decision underscores the ongoing tensions between constitutional recognition of Aboriginal and Treaty rights under section 35 and the protection of individual rights and freedoms.

The existence of a self-government agreement or constitution setting out a First Nation’s governance system will not automatically negate the ability of individual First Nation members to seek redress for discriminatory treatment under the Charter.

In dealing with this tension, however, the Court’s decision to apply the Charter to the Vuntut Gwitchin Constitution has potentially wide-ranging implications for the meaningful recognition of Indigenous Peoples' law and jurisdiction.

For Indigenous signatories to modern treaties, difficult decisions and numerous compromises are made during the treaty negotiations. The driver for many First Nations is the understanding that, at the end of that seemingly endless process, their inherent right to govern themselves will be recognized and respected. However, as the Dickson decision demonstrates, even with modern treaties in place, the result may only be partial recognition of Indigenous law and jurisdiction.

After years of negotiating its land claim and self-government agreements, Vuntut Gwitchin enacted its own Constitution which provided for the selection of political leaders based on their traditional laws and practices and in accordance with their recognized right of self-government. Notably, the Vuntut Gwitchin Constitution included a process for reviewing its internal governance practices and laws to ensure that the rights of its citizens were respected.

Rather than directing that concerns regarding the residency requirement be addressed under that process, however, the Court ultimately held that the Charter applied to the Vuntut Gwitchin Constitution because the Vuntut Gwitchin Constitution was subject to the self-government agreement, which in turn was negotiated within the limits of the Constitution of Canada.

In coming to this decision, the Court further commented that section 25 of the Charter provided “space” for Vuntut Gwitchin “to protect, preserve and promote the identity of their citizens through unique institutions, norms and government practices.” Interestingly, this appears to be exactly what Vuntut Gwitchin had intended by enacting its own Constitution, governance structures and laws in the first place.

Photo Credit: Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation

Looking ahead

For many non-Indigenous Canadians, the protection of an individual’s Charter rights and freedoms is so inviolable that any discussion of the Charter’s non-application is unimaginable. Indeed, the current iteration of Canada’s renewed comprehensive land claims policy requires that modern treaties confirm the application of the Charter to Indigenous Peoples.

The Charter has played a crucial role in protecting individual rights of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Canada in numerous situations. However, as courts continue to grapple with the inherent tensions between individual and collective rights, it is critical that they remain cognizant of the origin of section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 – to ensure the recognition and protection of the rights of Indigenous Peoples who lived and governed themselves according to their own laws long before the arrival of Europeans.

Failure to recognize the prior and continued existence of Indigenous law, including as expressed in modern treaties, when considering individual Charter claims risks undermining the purpose of section 35 and Indigenous Peoples’ longstanding, significant efforts to regain self-determination.

Angela D'Elia Decembrini is a lawyer at First Peoples Law Corporation.

Follow Angela on LinkedIn and Twitter

Kate Gunn is a lawyer at First Peoples Law Corporation. Kate completed her Master's of Law at the University of British Columbia. Her most recent academic essay, "Agreeing to Share: Treaty 3, History & the Courts," was published in the UBC Law Review.

Follow Kate on LinkedIn and Twitter

For more First Peoples Law analysis, visit our blog

Sign up for our Aboriginal Law Report