"The recovery of the people is tied to the recovery of food, since food itself is medicine: not only for the body, but for the soul, for the spiritual connection to history, ancestors, and the land."

Winona LaDuke, Recovering the Sacred: The Power of Naming and Claiming (2005)

For many Indigenous Peoples, the importance of food goes beyond its nutritional value.

Maintaining access to traditional food sources is inextricably linked to Indigenous Peoples’ relationships with the land and environment, the exercise of their Aboriginal title, rights and Treaty rights and the continuity of their cultures and traditions.

In recent months, concerns regarding food security have been heightened as COVID-19 related restrictions have placed increased pressure on food supply chains. For Indigenous communities across Canada, however, the pandemic has only exacerbated concerns about their already fragile food systems.

Given the complex relationships between Indigenous Peoples and their traditional food culture, it is not surprising that rising food security concerns have corresponded with a resurgence in the exercise of Indigenous food sovereignty--namely, the right of Indigenous Peoples to make decisions about and produce their own food.

Indigenous Food Insecurity

Food insecurity is defined as “the inadequate or unstable access to nutritious food due to financial constraints.” According to a 2019 study, 48 per cent of Indigenous households living on reserve and 23 per cent living off reserve face food insecurity, compared to a rate of 8.4 per cent for all households across Canada.

The disproportionate impact of food insecurity experienced by Indigenous households is in large part due to the wide-ranging impacts of colonialism on Indigenous Peoples. Marked by encroachment on their lands, destruction of traditional fishing, hunting and harvesting areas, populations weakened by disease, and the resulting loss of cultural knowledge, Canada’s colonial history has severely disrupted Indigenous Peoples’ relationship with their land-based food systems.

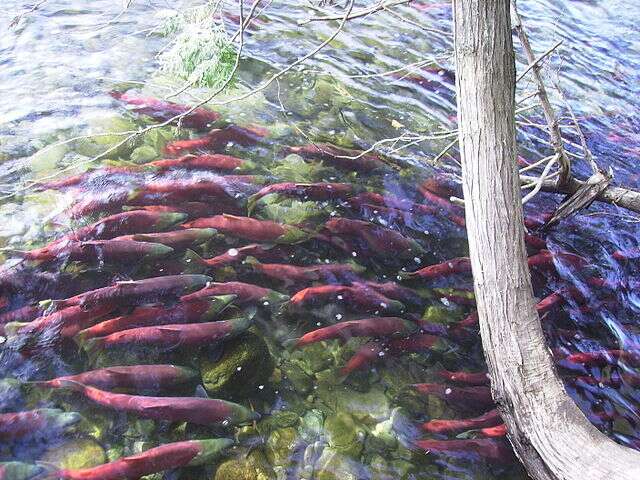

Today, the relationship between Indigenous Peoples and their traditional food sources is further hindered by the ongoing exploitation of Indigenous Peoples’ territory and infringement of their Aboriginal title and rights through industrial development and government mismanagement of resources. These activities impact the habitats of the animal and plant species relied on by Indigenous Peoples and threaten their land-based food systems.

For instance, the imposition of government-led conservation measures meant to protect species at risk are often misdirected and only serve to further limit the ability of Indigenous communities to exercise their fishing, hunting and harvesting rights within their territories. Further, while the Supreme Court of Canada has made clear that Indigenous food fisheries should have priority after conservation concerns have been addressed, in practice this has not always been the case.

Recent lockdown measures imposed as a result of COVID-19 and the inadequate response from government have only amplified food security concerns among Indigenous communities.

Indigenous Food Sovereignty

Indigenous food sovereignty aims to address the underlying issues affecting Indigenous Peoples and their ability to respond to the need for healthy, culturally appropriate foods, including by making decisions about the amount and quality of food they hunt, fish, gather, grow and eat.

Indigenous food sovereignty stems from Indigenous Peoples’ long-standing relationships with the land, forests, oceans and waters, and considers the interconnections between the cultural, political and environmental aspects of food systems. A resurgence in the Indigenous food sovereignty movement has developed in response to Indigenous food security concerns, as Indigenous Peoples seek to restore their relationships with the land and environment.

While the movement, at least in part, is focused on reforming food policy to incorporate Indigenous perspectives and address Indigenous concerns, community-based expressions of the movement, from the development of community gardens to calls for moratoriums on commercial fisheries to help restore fish stocks, can be found across Canada.

In response to heightened food security concerns in light of COVID-19, Indigenous Peoples have developed new ways to exercise their food self-determination to meet the changing needs of their communities. For some, this has involved limiting participation by members in fishing and hunting activities to ensure that physical distancing restrictions are adhered to.

Other examples include providing households with planter boxes, soil and seeds so members can establish “Granny Gardens” at home and reduce the number of trips to the grocery store. For others still, the focus has been on developing community-based food security plans which focus on the particular needs, traditions, geographic location and local food production capacity of the community with a view to reducing reliance on outside food sources.

Why it Matters

Over time, the decreased access by Indigenous Peoples to traditional foods has resulted in an increased reliance on industrialized food systems. This has led to a higher occurrence of food-related diseases among Indigenous populations. Awareness around the connection between diets focused on processed foods and chronic illness is becoming more widespread, especially as “eat local” and “slow food” trends become more popular within mainstream society.

Perhaps less obvious, however, is the way the loss of traditional food sources and practices also results in the loss of Indigenous Peoples’ traditional food knowledge, undermines their connection to the land and limits their ability to exercise their Aboriginal title, rights and Treaty rights.

For many Indigenous communities, the motivation to “eat local” is focused on the revival of their traditional food culture which has been subverted by colonialism and inherently racist policies.

At play is the interconnectedness of the cultural, environmental, political and legal aspects of Indigenous food systems. The exercise of food sovereignty provides an avenue to address each of these aspects.

Indigenous food sovereignty enables Indigenous Peoples to maintain their land stewardship practices while exercising the right to determine how they will nurture and practice healthy relationships with the land, plants and animals which in turn provide food for current and future generations.

As traditional food sources continue to be depleted through government mismanagement and unsustainable development practices, Indigenous Peoples’ fishing, hunting and harvesting rights are increasingly at risk of extinguishment. Indigenous food sovereignty promotes the recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ Aboriginal and Treaty rights and the importance of protecting and exercising these rights to preserve their traditional food culture.

Looking Ahead

The Indigenous food sovereignty movement is not new. The protection of Indigenous food systems is often at the heart of Indigenous Peoples’ ongoing struggle for the recognition and protection of their title and rights. The recent restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic have emphasized the urgent food security needs facing many Indigenous communities.

Immediate measures are required to address food security concerns. Indigenous food sovereignty provides the opportunity for Indigenous Peoples to be involved in the development and implementation of these measures in the short term.

Indigenous food sovereignty also aims to decolonize Canada’s food policies and encourages longer term approaches to strengthen Indigenous food systems and preserve traditional food sources. This responsibility, however, should not be treated as another “Indigenous issue” to be borne by Indigenous Peoples alone. This is a collective responsibility that must be shared by all Canadians.

Indigenous food sovereignty provides non-Indigenous people the opportunity to learn and understand the way the Canadian state has contributed to Indigenous Peoples’ fragile food systems, with all its ramifications, and to recognize Indigenous Peoples’ title and rights to the land as a way of moving forward. It calls on us to share in the responsibility of protecting the land and environment so that we may better support the preservation of Indigenous food systems.

Angela D'Elia Decembrini is a lawyer at First Peoples Law Corporation.

Follow Angela on LinkedIn and Twitter

For more First Peoples Law analysis, visit our blog

Sign up for our Aboriginal Law Report