You can read part one of Bruce's essay here.

Pity my high school French teacher. Fresh out of university and eager to establish herself in her profession she took a one-year placement teaching beginner French to kids from rural Manitoba whose aspirations rarely extended beyond gaining admission to the balcony at the town movie theatre.

When time travel is perfected, I will transport myself back to that blazing hot June day when, as with so many days that were to follow, accumulating like wrinkles that burrow into your vanity, I failed to be the person I wish I had been.

I would swap places with my fourteen-year old self, sliding into the desk with its authoritarian grip, part of a long line of desks that every minute of every school day transmitted into my muscles, into my bones, into my incubating self that an education was as wasted on me as seeds spread over rocks.

My adult self would possess words and experiences I lacked as a teenager. As if I had a marker that revealed secret messages, I would be able to read the pain and humiliation left behind by generations of children, who as adults, struggle to identify the distant moment when they saw their world of possibilities diminish like stars disappearing in the night sky.

My French teacher had endured eight months of verbal abuse. Teenagers—boys and girls—raised to identify the weak, timid and uncertain members of any herd, had pegged her as an outsider passing through and without local support and protection. She could be tormented without fear of consequence. There would be no older sibling or cousin prowling the schoolyard during recess itching to put a beating on you for daring to mess with one of theirs.

With the end of the school year taking shape like a grain elevator on the horizon, she finally lost her cool. One of my larger classmates, tall enough to peer over the bathroom stall doors and muscles developed beyond their years through unloading trucks filled with 50-pound bags of fertilizer, uttered something forgettable but momentous. Like a seemingly insignificant whisper of wind that lights a dormant ember, his inane insult touched a hidden vestige of willpower that flared up to shock us all.

Perhaps it wasn’t what he said as much as the dismissive turning of his back on her and striding towards the classroom door that set her off. To our surprise, she jumped to her feet, bolted from behind her desk, and ran after him. As he reached for the doorknob she leapt on his back, wrapped her arms around his neck and legs around his torso, threw her head back and released a long scream of humiliation as he raced out the door and down the hallway.

That was my experience learning French.

While the story of my grade nine teacher is extreme, most of those of my generation who come from a similar background have their own stories of the futility of trying to learn a second language as a child. This is especially the case for Indigenous children from rural and Indian Reserve families in the north and western Canada. This continues to be the case today. While the overall learning experience might have improved, only someone willfully blind to the disparity of educational opportunities across Canada would assume every child has an equal opportunity to become fluent in French.

The Divide

In much of Canada, the opportunity to learn French as a child turns on a socio-economic and urban/rural divide.

I recently relived the moment my high school French teacher lost her composure, as you experience a long ago injury when your fingers slide over a scar that has faded but will never disappear. It came back to me unexpectedly, after the dinner plates were cleared away and my wife squeezed up close to our children around our breakfast nook in East Vancouver. The pounding of my classmate's runners on the concrete floor, my teacher's scream, our frozen stares--unified by the realization we had gone too far--pressed me back against my kitchen counter as I watched my wife help our children with their French reading.

All three of our children will be fluent in French because they have advantages many children don't. Instead of attending a school a block from our house, they attend a French immersion school in a different catchment area. They have that opportunity because our oldest child won the lottery for a much sought after spot in French immersion. My two younger children didn't have to win the lottery--the school division has a policy of keeping families together in the same school.

My children are able to attend French immersion because my family has the time and resources to drive our kids to school. Among their classmates, my children have the added advantage of a parent who speaks French fluently because my wife, although of Irish-Anglo heritage, was raised in Ottawa and as a child attended one of the country's first French Immersion schools.

In much of Canada, learning French as a child is predominantly the preserve of middle-class, urban families. Even for those families, demand outstrips opportunities.

The History

Along with the socio-economic and urban/rural divide, there is a deeper historical aspect to the French language requirement.

When my 8-year old daughter speaks to me in her second language my blank stare disrupts her assumption that our family unit is indivisible. She realizes that along with her mother and siblings, she inhabits a world that excludes me. She fixes me with the look she gives our fish, hoping for a response as they stare back from the other side of the glass. In that moment of separation I think of how I’m an anomaly on my family tree.

Most of my ancestors who participated in the fur trade, Indigenous women (mostly Anishinaabe and Cree) and European men (English, French and Scottish), were multi-lingual. To a greater or lesser extent, they spoke Anishinaabemowin, Cree, English and French.

My paternal great-grandfather, Murdock McIvor, is an example. In 1852, during the Highland Clearances, he left his parents’ crofter home on the Isle of Lewis in Scotland’s Outer Hebrides. At the age of 22 he signed on with the Hudson's Bay Company and sailed from Stromness, Orkney to Moose Factory on James Bay. For the next 40 years he worked as a labourer and interpreter at fur trade posts in Quebec, Manitoba and Ontario. He spoke his native Gaelic, English and Anishinaabemowin and probably Cree and Oji-Cree. In 1863 he married Frances Muir (a Métis woman) and the two of them began raising a family in the Red River settlement. My grandfather, Colin, was born three years later at St. Peters on the Red River, north of present-day Winnipeg.

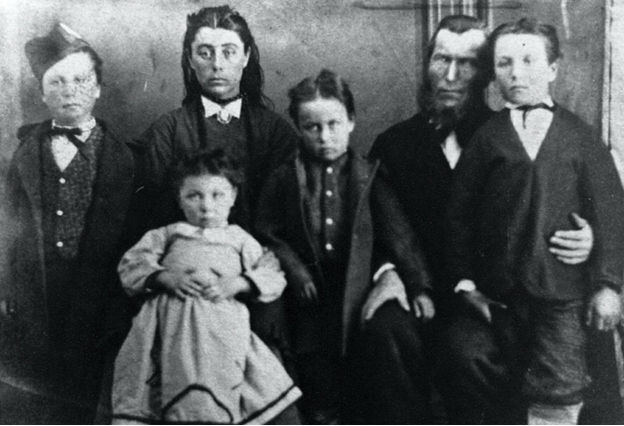

My great-grandparents, Frances and Murdock, with their children (from left to right) Colin, Elizabeth, Duncan and John James. (Photo courtesy of Greg Mogenson)

The late-19th century was a time of violent transition on the Canadian prairies. With the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway in the 1880s English-speaking colonizers from southern Ontario arrived in Western Canada in unprecedented numbers. They brought with them an intolerance for Indigenous people and a mono-lingual culture. They worked aggressively to stamp out the use of French and Indigenous languages. My family's history is representative of this change. Where my great-grandparents Frances and Murdock, spoke several languages, their son, Colin, raised on a farm on the shores of the Red River, only spoke English.

My mother's family history follows a similar linguistic path. My mother is descended from two of the oldest French families in Canada. They arrived in the 1630s, the Doucets in modern-day Nova Scotia and the Côtés in Quebec. For ten generations, through the Acadian Expulsion, the Battle of Quebec, jobs in New England textile mills, their migration west to Michigan, on to North Dakota, and then back to Canada, they spoke French as a first language. Because of the large Ukrainian population in southern Manitoba in the early 20th century, my maternal grandfather spoke French, English and Ukrainian.

By the time my mother attended grade school in rural Manitoba in the early 1940s a major change had occurred. The Manitoba Liberal government had outlawed teaching French in schools or even using it as a language of instruction. While my mother struggled to learn English in school, she continued to speak French with her family at home. Gradually, inevitably French became a private, not a public language. When she married my Scottish-Métis father, in deference to his inability to speak French, she stopped speaking it at home. My only childhood memories of French spoken at home are from when, in response to some mischief perpetrated by my siblings or myself, a French expletive would explode from my mother's lips.

One of the ironies of the argument that the French language requirement is necessary to respect the historical reality of Canada’s supposed ‘two founding nations,’ is that one of those nations, the English, have a long history of oppressing the learning of French in much of Canada. That shameful legacy is part of our present-day reality.

The Racism

The final issue I want to consider is the most difficult to describe, but likely the most powerful: how racism works to undermine confidence and limit horizons and opportunities.

Just as Indigenous children learn from an early age of the threat of violence perpetrated against them by non-Indigenous people, they are taught by many educators, either implicitly or explicitly, that they exist on the outside of the larger world and educational opportunities. They are labeled as trouble-makers and ‘good-for-nothings’ without a future. Many dedicated teachers do their best to support Indigenous children, but Indigenous parents know that their children experience racism and systemic barriers all too similar to what they experienced as children.

As I explained in Part One of this essay, I support the requirement for reserved seats for Quebec on the Supreme Court of Canada. The rationale that justifies those seats should apply to ensure there are an equal number of reserved seats for Indigenous Peoples.

I do not support the current government’s policy that Supreme Court justices be functionally bilingual in French. (When I mention it to law students from the European Union they stare at me in disbelief: “Does Canada not know about modern simultaneous translation?”). The requirement doesn’t affect me because I’ve never aspired to be a judge, but it does disqualify many otherwise qualified candidates, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, who have not had the opportunity, privilege and luxury to learn French.

More fundamentally, I oppose the requirement because I oppose all modern-day systems of domination and oppression of Indigenous people. The early-20th century Manitoba Liberal government of Tobias Norris used the law to oppress French and Indigenous people. The modern-day federal Liberal government employs the myth of ‘two founding nations’ to justify a policy that oppresses Indigenous people.

Over the last three decades I’ve witnessed the steady erosion of Indigenous Peoples’ confidence in the Canadian legal system. One reason is that Indigenous people do not see themselves, their values and lived experiences sufficiently represented in the Canadian judiciary, including the Supreme Court. While Justice O’Bonsawin’s appointment is welcomed, it underscores how different her life story is from the majority of Indigenous people in Canada. As long as laws and policies exist that deny these differences, Canada will continue to fail to live up to the principles and values it espouses around the world. I urge you to tell your politicians you expect better of Canada and of them.

First Peoples Law LLP is a law firm dedicated to defending and advancing the rights of Indigenous Peoples. We work exclusively with Indigenous Peoples to defend their inherent and constitutionally protected title, rights and Treaty rights, uphold their Indigenous laws and governance and ensure economic prosperity for their current and future generations.

Bruce McIvor is partner at First Peoples Law LLP. Bruce's ancestors took Métis scrip at Red River in Manitoba. He holds a law degree, a Ph.D. in Aboriginal and environmental history, is a Fulbright Scholar and author of Standoff: Why Reconciliation Fails Indigenous People and How to Fix It. He is a member of the Manitoba Métis Federation.