Last week the BC Supreme Court released its long-awaited decision in the Blueberry River First Nations’ treaty infringement case.

The decision, Yahey v. British Columbia, comes at the end of a month which saw the discovery of the unmarked graves of hundreds of Indigenous children, the dismantling of racist historical monuments and calls to designate Canada Day a national day of mourning.

Like these events, the Court’s decision in Yahey should be taken as a call to action. Canadian governments must take immediate, concrete steps to address the legacy and ongoing reality of colonization, including by honouring and upholding the treaties on which much of Canada is based.

What it is about

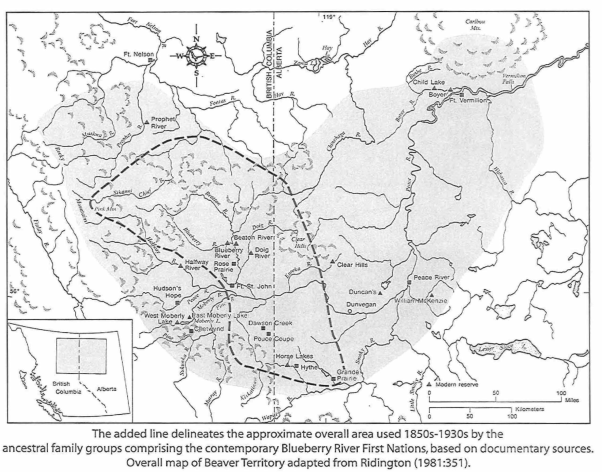

Blueberry is a Dane-zaa and Cree community located in the Upper Peace River region in what is now northeastern British Columbia.

In 1900 Blueberry’s ancestors adhered to Treaty 8. Like other Indigenous treaty parties, Blueberry understood that the treaty established a relationship of mutual respect and benefit, and that their lands and way of life would be protected from interference.

The written English text of the treaty provides that the government has a right to “take up” lands for settlement, mining, lumbering, trading and other purposes. The Crown also expressly promised the Indigenous treaty parties that they would be able to hunt and fish in their territories as if they never entered into treaty.

In recent decades, the Province of British Columbia authorized extensive industrial development, including oil and gas, forestry, mining and hydroelectric projects, in the Upper Peace River area. The cumulative effects of development left Blueberry members unable to exercise their rights in much of their territory.

In 2015 Blueberry brought an action against the Province on the basis that the Province breached Treaty 8 and infringed Blueberry’s treaty rights. The trial was heard over an 18-month period ending in November 2020.

Photo credit: Yahey at para 624

What the Court said

Critically, the Court rejected the Province’s position that the treaty was not infringed unless so much land was taken up that no meaningful ability to exercise the treaty right remained. The Court held that this would be contrary to the purpose of the treaty and would leave Blueberry with an “empty shell of a treaty promise.”

Instead, the Court found that the Province’s powers to take up lands under treaty must be exercised in a way that upholds the promises and protections in the treaty. The test for treaty infringement is not whether there is no ability left to exercise the rights at all, but whether a First Nation’s rights have been significantly diminished.

The Court held that the Province breached Treaty 8 and unjustifiably infringed Blueberry’s treaty rights by failing to protect those rights from the cumulative impacts of resource development.

The Court issued a declaration prohibiting the Province from authorizing further activities which infringe Blueberry’s rights. The prohibition is suspended for a 6-month period to provide the parties an opportunity to negotiate enforceable mechanisms to ensure Blueberry’s rights are recognized and protected.

Why it matters

Yahey marks the first time a court has directly considered the issue of the cumulative impacts of industrial development and treaty infringement. As such, the decision will have implications for First Nations across Canada and for other treaty cases now before the courts.

Importantly, the decision clarifies a fundamental misconception in Canadian law regarding governments’ power to take up treaty lands for resource development.

In its 2005 Mikisew decision, the Supreme Court of Canada held that not every government decision to take up lands under treaty constitutes an infringement requiring justification. Instead, the Supreme Court held that the government must act honourably and consult with First Nations when exercising the take up clause, and that a First Nation may have an action in treaty infringement if the government takes up so much land that there is no meaningful ability left to exercise the treaty rights.

Provincial governments across the country interpreted Mikisew as providing them free rein to develop resources on treaty lands, despite repeated calls from Indigenous people for the Crown to protect and uphold its treaty promises.

Yahey stands as a sharp reprimand to provincial governments. The Court confirmed that the provinces do not have an unfettered right to take up treaty lands and that treaty infringement lies on a spectrum. Consequently, governments may be liable for treaty infringement when they authorize development that significantly diminishes the First Nation’s ability to exercise a treaty right and long before the “no meaningful right” threshold is reached.

Looking ahead

The Blueberry decision unequivocally affirms that treaty rights must be protected and respected, and that there will be tangible consequences when governments fail to uphold the treaties. The decision joins a growing chorus of recent cases in which courts have called on the Crown to act now to honourably implement its treaties with Indigenous people.

The decision is also a reminder that the impacts of colonization -- including the devastating effects of Residential Schools on Indigenous children and families -- are rooted in the Crown’s assertion of control over Indigenous lands and its ongoing denial of Indigenous peoples’ inherent and treaty rights.

Reconciliation cannot take place unless governments take immediate steps to honour and uphold the Crown’s treaty promises. As the Court noted in Yahey, time is of the essence.

First Peoples Law LLP is a law firm dedicated to defending and advancing the rights of Indigenous Peoples. We work exclusively with Indigenous Peoples to defend their inherent and constitutionally protected title, rights and Treaty rights, uphold their Indigenous laws and governance and ensure economic prosperity for their current and future generations.

Kate Gunn is partner at First Peoples Law LLP. Kate completed her Master's of Law at the University of British Columbia. Her most recent academic essay, "Agreeing to Share: Treaty 3, History & the Courts," was published in the UBC Law Review.

Connect with Kate on LinkedIn and Twitter

For more First Peoples Law analysis, visit our blog

Sign up for our First Peoples Law Report