This fall has been marked with acts of violence and intimidation by non-Indigenous commercial fishers against members of the Mi’kmaq Nation in Nova Scotia seeking to carry out their treaty right to fish.

These actions, and the accompanying inaction on the part of law enforcement officials, are a stark reminder that racism remains a persistent part of Canadian society.

They also point to another significant barrier to the processes of decolonization and reconciliation – the ongoing failure of the federal and provincial governments in Canada to uphold and implement treaties between Indigenous Peoples and the Crown.

In this post, we examine current developments in relation to treaty rights and their implications for Indigenous Peoples.

Why are Treaty rights important?

For the past several decades, much of the development in the field of aboriginal law has focused on defining the scope of ‘aboriginal rights’ under section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982.

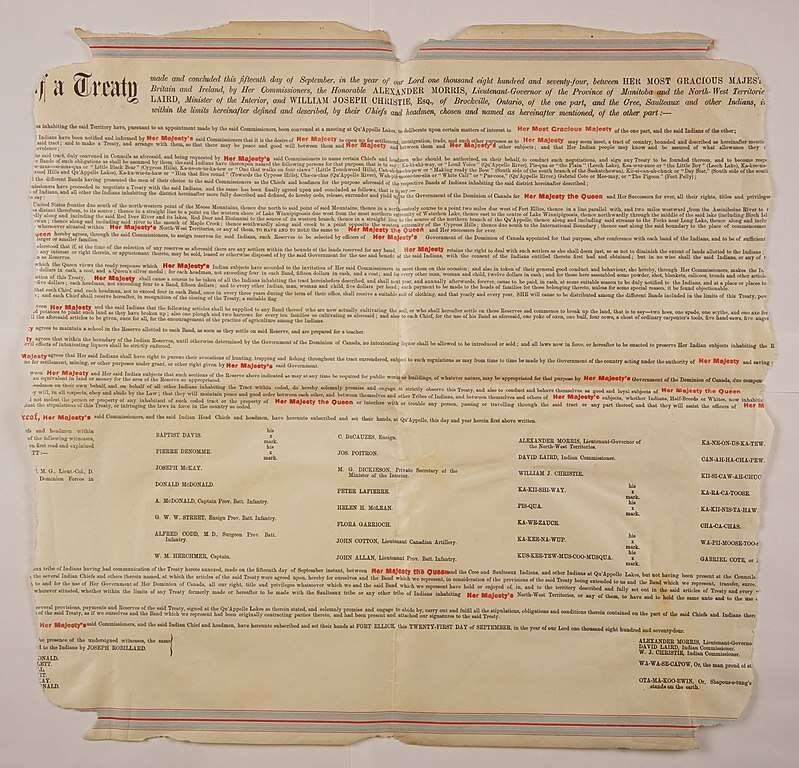

By contrast, relatively little attention has been paid to the rights guaranteed to Indigenous Peoples pursuant to their treaties with the Crown. This lack of attention obscures the fact that with the exception of British Columbia, most of the lands in what is now Canada are subject to Crown-Indigenous treaties.

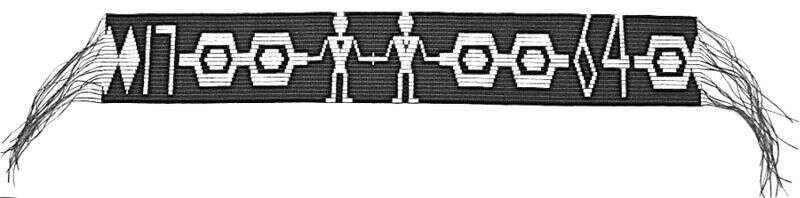

The negotiation of the treaties took place over hundreds of years. In many instances, they predate the formation of Canada. In Nova Scotia, where the current conflict is unfolding, representatives of the British Crown entered into ‘peace and friendship’ treaties in the 1700s directly with Indigenous Peoples on a Nation-to-Nation basis.

The relationships established under the treaties allowed for the expansion of European settlement into much of Canada. They continue to form the constitutional basis on which federal and provincial governments claim ownership and jurisdiction over most of Canada today.

In short, regardless of what part of the country we live in, the majority of non-Indigenous people in Canada owe their right to live here to these foundational agreements.

The existence of treaties and protections for treaty rights go hand in hand – that is, where lands are subject to treaties, the present-day descendants of the Indigenous treaty parties will hold constitutionally-protected rights, including, but not limited to, rights to hunt, fish and harvest.

Critically, these rights are not created by the treaties themselves. Treaty rights refer to the traditional, cultural, legal and economic activities of Indigenous Peoples that the Crown promised to safeguard in exchange for the Indigenous treaty parties’ agreement to allow settlers to live on and share their territories.

The flip side of treaty rights is the Crown’s treaty responsibilities, including the responsibility to ensure that their Indigenous treaty partners are able to exercise the rights guaranteed to them on entering into treaty now and into the future.

Interpreting the Treaties

The Crown and Indigenous treaty parties have sharply different views on the purpose and effect of the treaties.

Regardless of the written text, Indigenous Peoples have repeatedly and unequivocally expressed that their ancestors negotiated treaties to establish a relationship of peaceful co-existence with incoming settlers and that they did not surrender their rights to their territories.

At the same time, federal and provincial governments take the position that the Indigenous treaty parties surrendered their ownership of and jurisdiction over their lands on entering into treaty.

This divergence has led the Supreme Court to establish a set of principles specific to the interpretation of Crown-Indigenous treaties.

In interpreting the treaties, courts must take into account oral promises made during treaty negotiations, the perspective of the Indigenous treaty parties, as well as the historical and cultural context in which negotiations took place. Importantly, treaty rights such as trading are not frozen in time--they can be carried out in the present-day economy using new forms of technology and other means.

While the principles have been articulated in a number of cases, it is the Court's decision in Marshall – the case which affirmed the Mi’kmaq treaty right to sell and trade the products of their fishery – which is most often cited as a touchstone for treaty interpretation.

Ongoing misconceptions

Misconceptions abound among non-Indigenous people about the purpose and effect of the treaties as demonstrated by the violence and vigilantism now being carried out in Nova Scotia.

The root of this issue is not a lack of clarity in the law. The Supreme Court’s principles of treaty interpretation are well established. In the case of the Mi’kmaq, the particular right at issue was affirmed by the Court over two decades ago in Marshall.

The source of the ongoing conflict over treaties is the Crown’s failure to implement the treaties in a way that allows Indigenous Peoples to meaningfully exercise their constitutionally guaranteed rights.

The road ahead

Courts have been clear that it is incumbent on the Crown to fulfil its promises to Indigenous Peoples and make decisions in a way that advances the intended purposes of the treaties. It is not open to the Crown to ignore the treaties or avoid its obligations simply because it does not like the outcome or because the result will be unpopular among non-Indigenous people.

The events of this fall should remind us that it is time to call on federal and provincial governments to act honourably towards their Indigenous treaty partners and to fulfil the spirit and intent of the treaties in Mi’kma’ki and across the country.

Kate Gunn is a lawyer at First Peoples Law Corporation. Kate completed her Master's of Law at the University of British Columbia. Her most recent academic essay, "Agreeing to Share: Treaty 3, History & the Courts," was published in the UBC Law Review.

Follow Kate on LinkedIn and Twitter

Visit our blog for more First Peoples Law analysis

Sign up for our Aboriginal Law Report